Quick Recap: Foundation Concepts

In Part 1, we established the essential GPU architecture concepts:

We learned that naive GEMM kernels are memory-bound, not compute-bound. Today, we’ll discover why this happens by understanding the internal processing of Naive GEMM

Matrix Multiplication

Matrix Multiplication as we know has time complexity of O(N^3) , O(N^3) is not acceptable this definitely requires optimization, consider the scale of modern AI: a single attention mechanism in a large language model can involve large matrices and numerous matrix multipliations are involved across the layers of the models , If these core operations aren’t efficient even the most performant inference engines like vLLM or Triton can’t provide better results despite of the optimizations such as KV Cache, Prefill, Speculative Decoding etc…

The Computational Challenge

Let’s examine a concrete example. Consider multiplying two matrices: A (256×256) and B (256×256), resulting in matrix C (256×256).

To calculate any element C(i,j), we need to compute the dot product of row i from matrix A with column j from matrix B. For C(0,0), we multiply the first row of A with the first column of B and sum the results:

This requires 256 multiply-add operations. Since our result matrix has 256×256 = 65,536 elements, and each requires 256 operations, we need a total of 167,77,216 FMA (Fused Multiply-Add) operations.

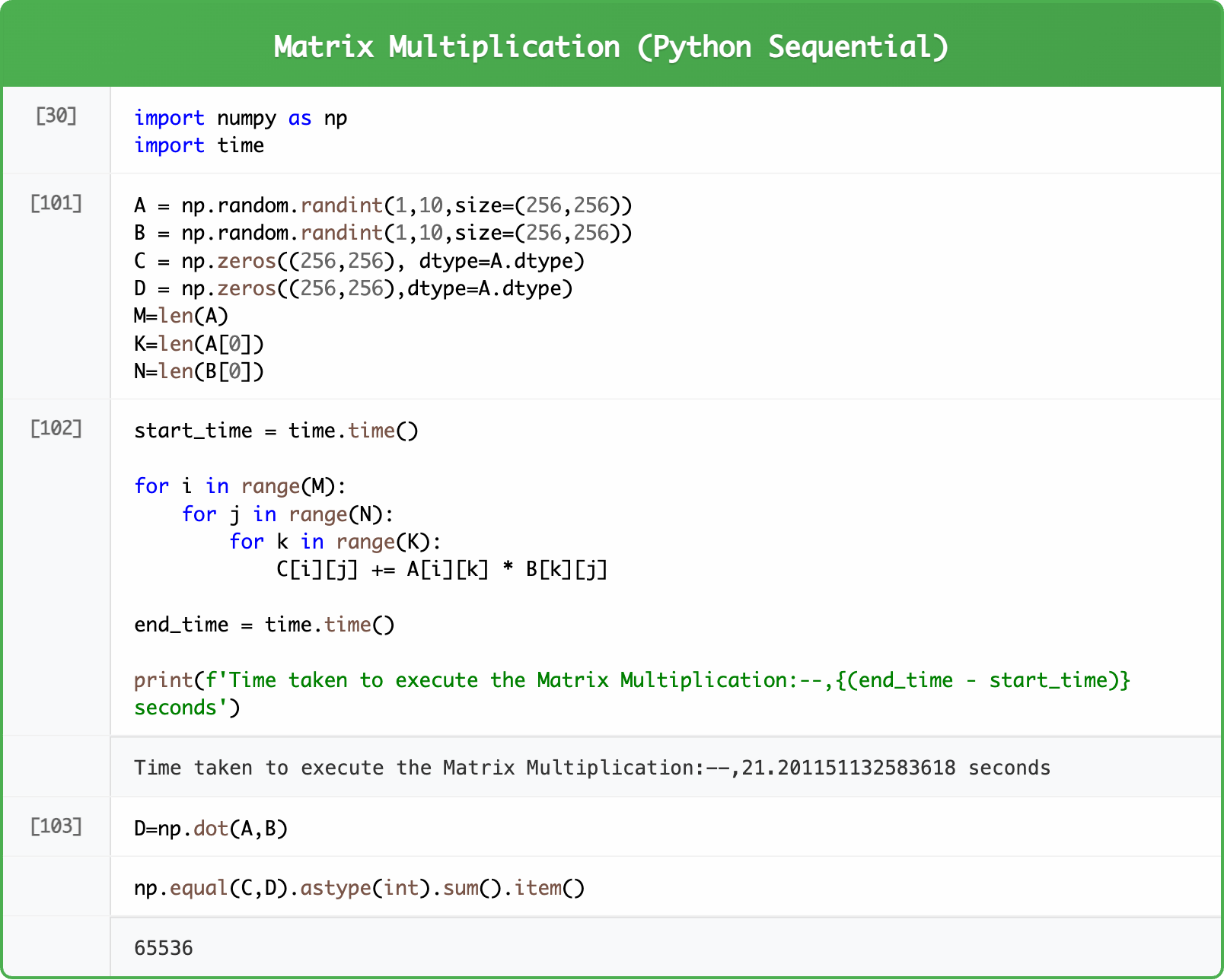

The Naive Sequential Approach (CPU)

The most straightforward implementation uses three nested loops: This sequential approach calculates elements one by one: C(0,0) → C(0,1) → … → C(255,255). On a modern CPU, this might take several seconds, which is unacceptable for real-time inference.

include visualization from Claude if possible

The Parallelization Opportunity

By knowing how matrix multiplication works we are certain that each element of the result matrix C can be calculated independently. Computing C(255,255) doesn’t depend on any previous calculations of matrix C. This independence is the foundation for parallelization.

Theoretically, we could spawn 65,536 threads—one for each result element. Thread-0 calculates C(0,0), Thread-1 calculates C(0,1), and so on. If we could execute all threads simultaneously, our computation time would be determined by the maximum time to perform 256 FMA operations rather than 8+ million.

Analogy

Manufacturing Plant that produces Cars, it requires the Skilled Technicians for assembling the Parts , the Technicians require Parts & Tools to assemble them as single Unit (Car)

Though I mentioned that we can parallelize the whole process by creating multiple threads one for each element, this has some constraints , to understand these constraints we need to understand GPU Architecture, in the next section we will try to understand minimum terminology that lays foundation for understanding the GEMM and Optimizations at different levels.

Naive CUDA Kernel

Configurations for Kernel Launch

Grid and dimensional block configurations can be set using different combinations. The general convention for grid configuration is as follows. For this example, we are considering the configuration blockDim(32,32):

gridDim((N+blockDim.x-1)/blockDim.x, (N+blockDim.y-1)/blockDim.y))

Dissecting Naive GEMM:

Memory Access Patterns and Coalescing Analysis:

When executing the line below, data must be loaded from matrices A and B following the A100’s memory hierarchy:

acc += A[row * K + k] * B[k * N + col]

-

The system searches through each level sequentially:

- Shared Memory (up to 164KB per SM, shared across all threads in a thread block)

- L1 Cache (28KB per SM when shared memory is maximized, shared across thread blocks)

- L2 Cache (40MB shared across all 108 SMs)

- HBM2 (slowest memory, 1.6TB/s bandwidth)

-

Memory Transaction Fundamentals: When loading data (e.g., A[row*K+k]), the memory subsystem doesn’t load just 4 bytes. Instead, it loads 128 bytes from consecutive memory locations in a single transaction. For optimal performance, threads in a warp should access consecutive memory locations. This is where memory coalescing becomes crucial—proper coalescing allows multiple threads to utilize a single 128-byte transaction, avoiding additional round trips to global memory.

Access Pattern Analysis for Warp-0:

-

Matrix A Access: The first warp, iterating through the K dimension across all iterations, accesses elements A[0] through A[255], totaling 256 elements × 4 bytes = 1KB of data. During each iteration, all threads in the warp access the same element of Matrix A, resulting in a broadcast pattern where one value is distributed to all 32 threads.

-

Matrix B Access: All 32 threads access consecutive elements B[0] through B[31] during the first iteration. Across 256 iterations along the K dimension, this represents 256 × 32 elements × 4 bytes = 32KB of data. Since each thread in the warp accesses consecutive memory locations, this achieves proper memory coalescing.

Cache Reality vs. Reuse Potential:

Though we are able to achieve coalescing memory access for Matrix B, we still have constraints on GPU resources limiting our potential to achieve optimal performance for GEMM.

In A100 GPU Architecture, total memory available for Shared Memory + L1 Cache is 192KB, with a maximum of 164KB allocatable to shared memory, leaving 28KB for L1 cache.

From our calculations for Warp-0, we know that this warp alone requires 33KB of data (1KB for Matrix A + 32KB for Matrix B). Since a thread block contains 8 warps, and multiple thread blocks may be scheduled on the same SM (sharing L1 cache), cache pressure becomes significant. This leads to frequent cache evictions, forcing us towards inefficient memory transactions to global memory.

Data Reuse Opportunities and Cache Limitations:

-

Each element A[i,k] should theoretically be reused across multiple output calculations. For example, A[0][k] values are needed by all warps calculating row 0 outputs across different columns.

-

Each element B[k,j] should be reused across multiple row calculations. For instance, B[k][0] is needed by multiple thread blocks calculating different rows of the same column.

Cache Reality: With only 28KB L1 cache available and 33KB+ data requirements per warp, most data gets evicted before it can be reused. When Warp-1 needs the same A[0][k] elements that Warp-0 just used, these elements are likely already evicted from cache, forcing expensive global memory accesses.

Naive GEMM Code

Summary

Issues with Naive GEMM

Naive GEMM achieves optimal memory access patterns (broadcast reads for Matrix A, coalesced reads for Matrix B) but suffers from poor data reuse due to cache limitations. Frequent evictions force repeated global memory fetches, resulting in memory-bound performance

Optimization Strategy:

Shared memory tiling will enable explicit data reuse management, transforming this memory-bound kernel into a compute-bound implementation.

References:

https://doc.sling.si/en/workshops/programming-gpu-cuda/02-GPU/02-memmodel/